Alex likes to read and think about things. Like wombats. Did you know wombats have upside-down pouches? It’s to keep dirt off their babies while they dig underground. Keep reading, kids. It’s how you learn things!

Alex likes to read and think about things. Like wombats. Did you know wombats have upside-down pouches? It’s to keep dirt off their babies while they dig underground. Keep reading, kids. It’s how you learn things!

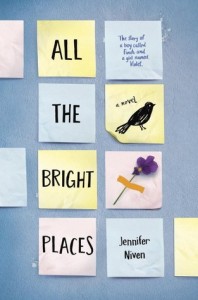

I went into All the Bright Places by Jennifer Niven with my guard up. No matter how good or bad the book was, I knew a story about depression was likely to trigger my own. No surprise, it did. All the Bright Places is a beautifully written book that is, at times, very difficult to read. I’d like to warn the reader up front that this review will have some pretty big spoilers.

I went into All the Bright Places by Jennifer Niven with my guard up. No matter how good or bad the book was, I knew a story about depression was likely to trigger my own. No surprise, it did. All the Bright Places is a beautifully written book that is, at times, very difficult to read. I’d like to warn the reader up front that this review will have some pretty big spoilers.

All the Bright Places is about two teens with depression. Violet’s sister died in a car accident the previous year and Violet blames herself for it. Finch has a long history of acting out and having sudden extreme mood swings. It is heavily implied that he is also bi-polar. At the start of the book both teens have suicidal thoughts, but Finch manages to talk Violet off of a ledge and Violet becomes Finch’s new reason for living. From there the story becomes about their budding romance as well as their personal growth. They learn about themselves and each other while exploring the hidden wonders of Indiana.

Violet and Finch are both very well-written and developed characters. It’s interesting to see them evolve and to understand more of their personal histories. It’s poignant, slice-of-life stuff and the John Green comparisons are sure to pop up. As a representation of how it feels to be depressed, All the Bright Places does a great job. I connected with the way Finch needed to find an active reason to stay alive, how he regularly pushed himself to physical exertion to feel life pumping through him, but still couldn’t stop himself from thinking about all the ways people have killed themselves. It’s a great illustration of the contradictions that can fill a person with depression.

However, now we come to the book’s greatest flaw: this is not a book for people with depression. I would absolutely not recommend it for anyone with depression who was looking for representation. The problem, and this is the big spoiler I mentioned, is that one of the protagonists kills himself. I was worried about this for the entire book. I kept flipping ahead and peaking at the last page, knowing what I saw and hoping I was wrong.

Of the two, Finch is the character with the more deep-rooted mental issues. It’s made clear through the book that he’s had suicidal thoughts for years, which hasn’t been made easier by years of bullying in school, an absent mother, and an abusive father. Being with Violet makes things better for a time, but as the book progresses I could see his dark thoughts coming back. In the end, he runs away from home and isn’t heard from for weeks. Finally Violet finds him, drowned in a lake where they’d had a date.

Suicide is a delicate topic to put in any story. Sometimes it’s used for sensationalism and sometimes it’s meant to illustrate poignant tragedy. In a book about depression though, it’s simply an essential element to discuss. Sadly, depression and suicide go together all too often in the real world. Unfortunately, Finch’s suicide is one that is handled poorly, ruining much of the book.

Once Finch dies, I feel that All the Bright Places really shows its true colors. I have seen this novel advertised as a story about teenage depression, but I don’t think that’s quite right. It’s a book for people with friends who commit suicide. The author admits at the end that it was an experience she went through herself and the last chunk of the story is all about Violet coping with losing Finch.

In his absence Finch goes from being an interesting, well-rounded character to a manic pixie dream-boy. Prior to killing himself he left all sort of special messages for Violet to find, final love letters to the wonder of their romance. During this section Violet doesn’t question what was going through Finch’s mind or the tragedy of suicide. Instead it’s all about finding the next whimsical message and ultimately giving Violet the strength to move on with her life.

It all left me incredibly sad and angry. Depression is a terrible illness that will regularly make a person believe the worst things about themself. It’s painful and it’s deadly and anyone with it knows that it’s daily struggle to find reasons to stay alive. Yes, there are wonderful people like Finch who lose that battle, but that isn’t the message that teens need to read about. What anyone with depression desperately needs is hope. We need to believe that we can get better, that we can get to a place somehow where we can function without that little voice saying “This would all be easier if you just died.” All the Bright Places does not leave the depressed reader with that hope. Instead it says, “If you die the right way, you can end up being an inspiration to others.”

The book also does an awful job of portraying the means to recovery for depression or any mental illness. In the fashion of any 90’s coming-of-age story, Violet and Finch both grow and evolve entirely through talking to each other, whimsical adventures, and abstract philosophy. While those things might help some people, things like therapy and medication are often essential. In All the Bright Places both standard treatment methods are shown in a very negative light. Therapists are well-meaning adults who don’t really understand at best, or at worst will put in minimal effort to try and get the depressed kid back in line. At one point Violet finds Finch living in his bedroom closet and suggests therapy to him, only to have him run away. That winds up being the last time she sees him. She partially blames herself for his death because she pushed him to seek help.

The only mention of medication comes when Finch drops in on a suicidal teens support group and sees several kids with “the dull, vacant look of people on drugs”. No one explains the benefits of antidepressants. Instead any hint of medical treatment is treated with disgust and outdated ideas. Finch says that medication will take away who you are or that or a medical label like “bipolar” will only reduce you to a crazy case-study. This notion is never refuted.

It’s painful because the writing and the characters are wonderfully well-crafted, but if you’re looking for a book about depression I’d pass on this one. The demonization of proper treatment, the presence of possibly preventable suicide, and the sudden transformation of Finch into a manic pixie dream-boy all weigh the story down too much. Save yourself the heartache and read something with a bit more hope.

S. Jae-Jones (called JJ)’s emotional growth was stunted at the age of 12, the age when adventures were imminent and romance just over the horizon. She lives in grits country, where she pretends to be an adult with a mortgage and a car. Other places to find JJ include

S. Jae-Jones (called JJ)’s emotional growth was stunted at the age of 12, the age when adventures were imminent and romance just over the horizon. She lives in grits country, where she pretends to be an adult with a mortgage and a car. Other places to find JJ include