Andrea Shettle, a program manager at the U.S. International Council on Disabilities (USICD), is passionate about disability rights both domestically and internationally. At USICD, she coordinates an internship program for students and recent graduates who aspire to careers in international development. She also assists with the national campaign for U.S. ratification of the international disability treaty, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). In her free time, she reads voraciously. She blogs (and reblogs from others) about disability rights, the CRPD, and disability representation in books and other media. She published a fantasy novel in 1990, Flute Song Magic, which is out of print. Find her on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Andrea Shettle, a program manager at the U.S. International Council on Disabilities (USICD), is passionate about disability rights both domestically and internationally. At USICD, she coordinates an internship program for students and recent graduates who aspire to careers in international development. She also assists with the national campaign for U.S. ratification of the international disability treaty, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). In her free time, she reads voraciously. She blogs (and reblogs from others) about disability rights, the CRPD, and disability representation in books and other media. She published a fantasy novel in 1990, Flute Song Magic, which is out of print. Find her on Twitter and LinkedIn.

On the rare occasions that I stumble across a book featuring a disabled character while browsing, I gravitate to it. But I also feel afraid. Afraid to invest my hope in finding characters I like only to feel betrayed—again—to find that the character most like me is just there as a prop for another character’s personal growth. Afraid to feel betrayed—again—by an author only interested in using disability as a metaphor for “broken” or “twisted” spirits. As if our bodies belonged to them to use as metaphor. As if either our bodies or our spirits were automatically broken or twisted just because we are people with disabilities.

On the rare occasions that I stumble across a book featuring a disabled character while browsing, I gravitate to it. But I also feel afraid. Afraid to invest my hope in finding characters I like only to feel betrayed—again—to find that the character most like me is just there as a prop for another character’s personal growth. Afraid to feel betrayed—again—by an author only interested in using disability as a metaphor for “broken” or “twisted” spirits. As if our bodies belonged to them to use as metaphor. As if either our bodies or our spirits were automatically broken or twisted just because we are people with disabilities.

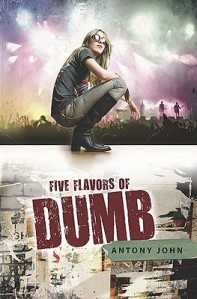

If you understand how badly disabled readers need to meet ourselves in a book, and if you also understand how often we’ve been betrayed, then perhaps you’ll understand the mingled excitement and trepidation with which I approached the task of reading Five Flavors of Dumb by Antony John. The protagonist, Piper Vaughan, is a young deaf woman finishing her last year of high school. She’s smart, academically successful, mainstreamed at a public high school, a wicked good chess player, and interested in attending Gallaudet University in part so she can finally be among other deaf signers like her. In these ways (apart from the chess) she is like me if you subtract a quarter century from my age.

In the story, Piper struggles to manage a new high school hard rock band called “Dumb”. Struggles, not because she is deaf, but because the band is comprised of members who do not always get along well. In the midst of all the drama involving “her” band, Piper also is figuring out how she wants to relate to her parents and her two siblings. The dynamics of how this plays out in the story is much influenced by Piper being deaf and her family hearing. But the dynamics are also much influenced by Piper being an ordinary adolescent figuring out who she wants to be as she emerges into adulthood.

If you’re just reading this review to know if there is a deaf/Deaf reader who is comfortable recommending this book as being largely free of stereotypes and other problematic representation, then here’s my short answer: Yes. Despite some flaws, it is clear the author did his research. I enjoyed this book and recommend it.

That’s the short answer. If you want analysis, this is where I get into that.

Let’s start with technical accuracy in portraying deafness. When dealing with things other than music, Antony John is pretty consistent in how he portrays Piper’s ability—and lack of ability—to hear the sounds around her. This is what makes it frustrating that he robs her of all ability to appreciate the music (or, as is often the case for this group of novice musicians, the chaotic noise) that the band, “Dumb”, produces.

Piper can hear well enough that her hearing aids significantly boost her ability to lip read others, at least in quiet situations where there aren’t other sounds to compete for attention. There is even one scene where she is able to catch a few words that another character speaks directly into her hearing aid even though she cannot see her face. Piper hears better than I do—just like plenty of real-life moderately deaf or hard of hearing people. Although I hear some loud, low pitched sounds and some limited speech, there’s nothing “moderate” about my hearing loss.

All this being the case, when Piper is standing close enough, she should be able to hear the sound of Josh singing even if she still misses what the words are. She should be able to hear Finn demonstrating a chord on his guitar even if she cannot reliably distinguish one chord from another or whether each chord sounds the way it should. And she also should be able to hear the band well enough to decide if she likes their music or not. In my case, I do hear music well enough—if well amplified—to know what I like and don’t like. And Dumb is never stingy with their amplification. Piper, who hears more than me, should be able to hear it also.

I think Antony John may have meant to amuse his hearing readers with the apparent “irony” of a deaf girl managing a band she cannot hear. Unfortunately he is apparently so enamored by this concept that he has allowed it to override the overall accuracy he otherwise achieved so well. If I had the power to direct a re-write, I would encourage him to consider either making her ability to hear and enjoy music more consistent for someone with a “moderately severe” hearing loss, or else making her more profoundly deaf (though the latter would mean making her less of a champion lip reader). I also would encourage him to consider the fact that there are many deaf people who love music even if they cannot hear it at all. They love the sensation of vibrations from a strong beat thrumming through their bodies, which can work well for hard rock and other loud, rhythmic music. And Anthony John does, in fact, sometimes describe Piper picking up the vibrations of the music in her body. So why should Piper be so alienated from the music that her band produces?

Despite this and some other minor issues, Antony John’s depiction of what it can be like to be deaf is still mostly on target. There are many little things he gets right, like Piper needing to remove her hearing aids before a hair stylist starts to wash her hair, or the fact that it’s easier to lip read people when they’re directly across the table from you than it is if they were next to you.

Although the author does fall for the tiresome trope of the champion deaf lip reader, Piper’s lip reading abilities are nevertheless largely consistent with her level of hearing loss. I also count in his favor that Antony John manage to show that lip reading isn’t an easy task even for a champion like Piper. She misses a homework assignment when the teacher’s announcement competes with the sounds of other students preparing to leave class. She has trouble understanding speech in the poor acoustic environment of the girl’s bathroom. It comes clearly that even a stellar lip reader is still working their butt off to make it work. It is clear why Piper prefers to use sign language when the opportunity is available.

Other things I like: Antony John avoids the trope of a single disabled character alienated from the disability community. Although she is apparently the only deaf student at her school, Piper does have a deaf friend who, like her, feels most comfortable signing. Granted, this is a friend who has moved away, which means Piper can only chat with her via computer. But it’s nice to see validation of the fact that many people with disabilities, particularly signing culturally Deaf people, have connections to others who share their disability and highly value these connections.

Antony John’s depiction of how hearing people react to Piper’s deafness is also true to life. Some, like Ed, seem comfortable with whom she is and adapt easily to her communication needs. A few other characters are obnoxious jerks who patronize Piper and underestimate her capabilities. And many characters are trying to do the right thing—at least sometimes—but are still somewhat clueless. This mix of reactions can be tricky to get right in fiction. I’ve seen other efforts that either have their disabled characters living in an unrealistically inclusive utopia, or else there might be one scene with clumsily blatant prejudice that does little to give a sense for the pervasiveness of micro-aggressions toward deaf people in daily life. Antony John steers the balance between these extremes well.

I also like the balance Antony John strikes between showing both Piper’s limitations as a deaf manager of a rock band and the strengths she is able to use to evade these limitations. She cannot, for example, realize without being told that the band only knows how to play songs that use a specific sequence of three chords. But she recruits her brother, Finn, and her friend, Ed, to help identify these and other weaknesses she cannot assess on her own. Meanwhile, Piper discovers a knack for marketing the band and negotiating deals. She also is able to “read” the dysfunctional relationships among the band members through sharp-eyed observation of facial expressions and body language, even in contexts where she cannot understand everything they say. She sometimes stumbles in managing these relationships—as you would expect from a young, inexperienced adult. But she learns from her mistakes.

Here, let’s shift gears to look at other kinds of diversity. The cast of Five Flavors is almost exclusively white, cis, and straight with the story set in a “predominantly white, middle-class suburb of Seattle”. There is only one important character, described as having dark skin, whose mother is African American. There is one other major character, Ed, whose last name is Chen. Otherwise, there is little racial or ethnic diversity, even among minor characters. It seems we are meant to read characters as white unless told otherwise.

Also, apart from Piper’s family temporary money issues, most characters seem to be either middle class or wealthy. Poverty is only addressed when the characters visit the old homes of rock stars. Antony John’s language often becomes lurid in passages that talk about poverty. I usually found myself feeling uncomfortable while reading these passages. They made me wonder if the way he writes about poverty is what some poor people have meant when describing the sensation of having their stories presented to the world as a form of “poverty porn.” Meaning, packaged to elicit emotional responses from people who haven’t experienced poverty without consideration for how poor people feel about their own experiences or about the presentation of their stories.

I think Antony John means for his descriptions of the former poverty of rock stars to elevate the importance of rock music for readers. But if so, these don’t have that effect for me. There were other scenes, in which characters talk about the personal meaning of certain pieces of music to them or in which characters react to the music they are listening to, that I felt were much more effective.

Despite my criticisms, I enjoyed getting to know Piper through this book and watching her grow as a problem solver, as a rock band manager, as a sister and daughter and friend. Although this book was weak in other areas of diversity, I feel that Antony John did a solid job of handling a deaf protagonist and hope he will consider writing more novels with disabled characters in the future—perhaps including a sequel to Five Flavors of Dumb.