Elise Phalen just graduated from Boston University with a degree in English Literature. She was diagnosed with epilepsy at 11, and is more than happy to answer your questions about it. Originally from Arizona, she has travelled the world, studying and living in Hermosillo, Mexico and Grenoble, France as well as interning at the 2013 Sydney Writers’ Festival in Australia. Elise is now back in the Boston area and divides her time between making coffee at Starbucks, working at the public library, and fretting about the future.

Elise Phalen just graduated from Boston University with a degree in English Literature. She was diagnosed with epilepsy at 11, and is more than happy to answer your questions about it. Originally from Arizona, she has travelled the world, studying and living in Hermosillo, Mexico and Grenoble, France as well as interning at the 2013 Sydney Writers’ Festival in Australia. Elise is now back in the Boston area and divides her time between making coffee at Starbucks, working at the public library, and fretting about the future.

The first time I ever saw a character with epilepsy in literature, she eventually turned evil, cut off someone’s head in an ancient magic ritual, and then died in a burning castle.

The first time I ever saw a character with epilepsy in literature, she eventually turned evil, cut off someone’s head in an ancient magic ritual, and then died in a burning castle.

I was diagnosed with epilepsy at eleven and have had grand mal seizures on and off over the past 11 years. Looking back on that first reading, I am troubled that she met such an unfortunate end. But at the time I was ecstatic. It was life changing. My experiences existed in the fictional world. I was worth thinking about and my problems were worth writing about. The next time I saw a character with epilepsy in young adult literature, it was the narrator of 100 Sideways Miles, which I read almost seven years later.

In between these two readings, I mostly saw seizures on TV shows where the first aid was always wrong (I’m looking at you, Teen Wolf and Orphan Black). There are also the handfuls of upsetting moments when a character would dance badly and the other characters would laugh and compare their lack of rhythm to having a seizure. I would cringe as it hit me viscerally, wishing that I could scratch the words off the page and out of my memory.

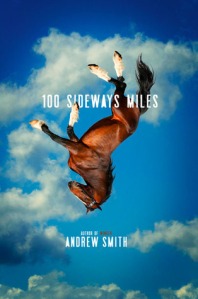

Andrew Smith’s 100 Sideways Miles is essentially a bildungsroman, a coming of age story, about a boy, Finn, who goes on a road trip and comes to understand that he is still “too young and too stupid” and that the journey of coming of age is never really complete. Finn’s journey is also one towards coming to terms with his body and his autonomy, as connected to his epilepsy.

Epilepsy is a very complicated condition that no one experiences in exactly the same way, so Smith gets some leeway in how he portrays Finn’s seizures. But it was respectful and well researched in a way that I had never seen before. Smith did not ignore the importance of first aid or the realities people with epilepsy face on a regular basis. Finn experiences non-convulsive partial seizures and he faces them as something scary but somehow beautiful:

I am just standing there, and first I smell something sweet – like flowers or maple syrup. Then I realize that I don’t know the names for anything I am looking at…Sounds, colors, textures, all mash together in an enormous symphonic assault on my senses as I shrink down, smaller and smaller. I am not hot, cold, dizzy, or uncomfortable—because all of those things are words, which by that point the seizure have all floated away…It is all so beautiful.

Finn’s “atoms drift apart” and he is at the whim of the new world his seizure has created. For me, who has seizures primarily while I sleep, this haunted me in how much it resembled a reversed version of how I regain consciousness.

Smith does a good job for the most part of balancing a respectful portrayal of a complicated condition and accurately portraying the realities that accompany it. Smith is respectful, but Finn is angry. His anger manifests as outbursts following his episodes, and is generally accompanied by the panging guilt of lashing out at the people who care about you over something that neither of you can control.

In the plot, Finn’s seizures serve as a physical manifestation of his fear that he is stuck in the book his father wrote which contains a character clearly based on him. He feels out of control of his life and his destiny and attempts to reconcile his lack of bodily autonomy by taking control of the way he perceives the world, such as measuring in minutes instead of miles. Connecting disability to metaphor is difficult terrain to tread, but Smith does his best. Finn’s epilepsy is portrayed in its own right as an important part of his character and I felt it came across as a piece of what makes him who he is rather than simply a plot device.

The question of fate and autonomy is a prominent theme of 100 Sideways Miles. These issues are a huge part of my daily life: “Do I just have a headache or did I have a seizure in my sleep last night?” and waiting a full day after a seizure for my full motor capacity to return. It was nice to see that Smith didn’t shy away from the things that are real and scary about epilepsy and how it dictates your relationship with your body.

Treating a disability with thoughtfulness and respect goes beyond the plot and the metaphorical implications. It’s also the little things that matter and make it feel real, especially to those of us who actually live with that disability. Smith does not ignore that the frequency of Finn’s seizures have precluded him from learning how to drive. He portrays the desire to avoid the subject with strangers alongside the need for people to know how to deal with it in case he has an episode around them. I enjoyed the way that Finn dealt with these issues with equal parts awkwardness and bravery.

The book’s only truly distasteful moment for me came in the scene when his love interest Julia found him on his front porch after a particularly bad episode and later made a joke about possibly having taken a picture of his naked, unconscious body. With trends of this sort of things actually happening via social media lately, it was a vicious joke that I wish had not been included.

Beyond that disturbing scene, Smith left some key things out of his portrayal of the epilepsy experience. The most glaring thing missing was any mention of long-term medical treatment. Finn has no regular neurologist and doesn’t take any medication. I kept waiting for him to take his medicine or complain about the tedium of medical treatment, but it never came. My other disappointment was not Smith’s fault, but the choice on the part of his publisher not to include Finn’s epilepsy in the blurb on the back cover. How will my fellow epilepsy pals know that Finn is there if no one is telling them? This oversight reeks of ableism and shame when they should be proud of their epileptic boy and his grand adventure.

All in all, 100 Sideways Miles is not a perfect portrayal of what it means to have epilepsy. But it is respectful and spoke to me on unexpected levels. The story itself is a ton of fun and I enjoyed Finn and all his quirks. 100 Sideways Miles did its best and opened up doors for people to see epilepsy in fiction and to continue to think and write about it meaningfully. And hey, at least no one turned evil and died in a magical burning castle.